The way biblical texts marked time—whether it be days, weeks, months, or years—laid the foundations for the way we think about time today.

When did the day start?

Today, a normal day begins in the morning, and this was probably true for ancient Israelites. For example, the creation story in Gen 1 describes the working day as beginning in the morning (see also Judg 19:4–9). The priests in the temple also began their day in the morning (Lev 7:15–18). However, late layers of the Hebrew Bible suggest that the day began at sunset. Exodus 12:18, for instance, defines the Feast of Unleavened Bread from sunset to sunset (see also Lev 23:32). The idea that the day began at sunset aligned with practices in neighboring Mesopotamian cultures and became the standard practice in later Jewish tradition.

How was the week measured?

Ancient peoples used different systems to measure time shorter than a month. Some biblical texts, for instance, attest to the use of a ten-day period for domestic but also cultic purposes (Gen 24:55, Exod 12:3). Small calendar plaques found in Iron Age Judah support this finding. The plaques, found in Lachish, Jerusalem, Aroer, and other Judean sites, provide a graphic demonstration of the month using three lines of ten perforated holes, meant for inserting a peg and advancing it through the days of the month. One tablet adds a line of twelve holes to mark the months of the year. The plaques were used by administrators as desk calendars. However, the concept of the week, a unit of seven days, is particularly significant in the Bible.

Each week ended with the Sabbath, a day of rest and worship. The term šbt earlier on may have indicated the day of Full Moon, like the Akkadian term šapattu. But the Sabbath was an innovation in the ancient Near Eastern environment. Neighboring Mesopotamian cultures did not use a seven-day week but instead celebrated festivals at various points throughout the month. The Bible emphasizes the number seven as a sacred number and assigns the Sabbath a central role in the world’s order. During the Babylonian exile, the Sabbath became a key part of Jewish life. Texts like Isa 58:13–14 and Neh 13:15–22 stressed the importance of keeping the Sabbath as a sign of Jewish identity.

Priestly authors used the week to create a sense of sacred time. They established seven weeks between harvest festivals (Lev 23:15–16). This practice was later extended in the Temple Scroll from Qumran, which added even more harvest festivals, all connected by the number seven. The number seven was also used to establish important dates like the Jubilee year, a special year that followed seven sets of seven years (Lev 25). Hints of even longer weekly counts, covering many years, appear in Lev 26:34–35. The book of Jubilees, written in the Hellenistic period, frames the entire sequence of patriarchal history as a series of weeks, years, and jubilees.

However, the exact way to count the “sabbatical” festivals became a topic of debate in Second Temple times. For instance, the book of Leviticus says that one should offer the “first fruits of the harvest” to the priest, but the date for this “omer offering” is not specified; it simply states that it should be on “(the day) after the Sabbath” (Lev 23:11). Priestly sects celebrated this festival on Sunday. This practice required a count of seven full weeks between Sabbaths. In contrast, the Pharisees and later the rabbinic sages disconnected the date of the omer ritual from the days of the week, placing it after the first festival day of Passover.

By the first century BCE, the Sabbath began to be recognized in civil contracts and documents, marking its growing influence on daily life. Interestingly, the Roman culture also adopted a seven-day week at this time, geared to the seven planets, possibly influenced by Jewish customs.

What seasons and festivals does the Bible recognize?

The biblical year revolved around the changing seasons, particularly the autumn and spring equinoxes. The main festivals are arranged around them: Sukkot (the Festival of Ingathering) in the autumn and Pesah-Mazzot-Shavuot (the Festival of Harvest) in the spring. This pattern was similar to the practices in neighboring cultures, like those of the West Semitic and Mesopotamian peoples.

The spring and autumn festivals were preceded by special days of preparation. Sukkot was preceded by the “Day of Remembrance” or “Day of Blowing (the Shofar)” (Lev 23:24, Num 29:1), a festival that later became the Jewish New Year Day. Sukkot was also preceded by the Day of Atonement (Yom Hakkippurim) on the 10th day of the autumn month. This day, which had been a time for the ritual purification (kpr) of the temple (Lev 16:1–28), became the day of purgation for individual sins.

The spring festivals were also preceded by days of purification (Ezek 45:18–21 MT). The spring festivals celebrated the harvest and the first fruits. The first major spring event was the offering of the first sheaf of grain (Lev 23:10; see the omer offering above). The harvest season continued for seven weeks (Lev 23:15-17) until the Festival of Shavuot.

What were the months called?

The Bible does not always provide clear names for the months, especially in earlier periods. Some early sources, like 1 Kgs 6–8, use Phoenician names for months, connecting the practice to the cooperation between the Israelites and Phoenicians during the construction of Solomon’s temple. The Gezer Calendar, a famous tenth century BCE inscription, does not preserve month names. Instead, it lists agricultural activities throughout the year.

| Hebrew Bible | Phoenician | Hebrew Numbered | Babylonian | Gregorian |

| Nisan | 1st month | Nisanu | March–April | |

| Iyyar | Ziv | 2nd month | Ayyāru | April–May |

| Sivan | 3rd month | Simānu | May–June | |

| Tammuz | 4th month | Du’uzu | June–July | |

| Av | 5th month | Abu | July–August | |

| Elul | 6th month | Ululu | August–September | |

| Tishri | Ethanim | 7th month | Tashrītu | September–October |

| Cheshvan | Bul | 8th month | (W)Arahsamnu | October–November |

| Kislev | 9th month | Kislīmu | November–December | |

| Tevet | 10th month | Ṭebētu | December–January | |

| Shevat | 11th month | Šabāṭu | January–February | |

| Adar | 12th month | Addaru | February–March |

By the sixth century BCE, biblical texts used numbers for the months: first month, second, third et cetera, with the first month beginning in the spring (Exod 12:2). These numbers eventually gave way to the Babylonian-Aramaic month names (Tishri, Kislev, etc.). The meaning of these names was unknown to the Jews, but their usage became common over time, and they are still used used by Jews today. The first month in this system was Tishri in the autumn. This created tension with the priestly new year, which began in the spring.

In later texts (e.g., Est 8:9), both the numbered system and the Babylonian month names are used side by side. Books like 1 Maccabees and the book of Jubilees still used the numbered months, while others, like the Pharisaic Megillat Ta’anit, used Babylonian month names. Greek-speaking Jewish authors often coordinated the months with Macedonian or Roman month names (e.g., Josephus, A.J. 2:311).

What was the calendar like?

The Hebrew Bible does not emphasize the astronomical details of its calendar. Instead, it generally describes time as being marked by all luminaries: sun, moon, and stars (Gen 1:14). Various scholars have suggested a solar basis for early Israelite calendars, but they lack sufficient evidence to draw any firm conclusions. Administrators in Judah, like their earlier peers in Mesopotamia, envisioned thirty days per month, with twelve months in a year, but this system did not function as a real calendar. The most reasonable historical reconstruction is that early Israelites used a luni-solar calendar like their neighbors in Babylon and the Phoenician cities. With this calendar regulated by the reigning empires in Babylonia and Iran, there would have been no need to establish a distinctly Jewish calendar.

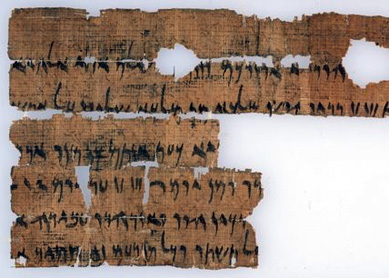

During the Hellenistic period, interest in astronomy grew and, with it, a more defined understanding of the calendar. The astronomical section of the book of Enoch (in Qumran fragments and later in 1 En. 72–82), whose roots lie in the third century BCE, introduced the idea of a 364-day year, which was further developed in the book of Jubilees (second century BCE). Jubilees’s calendar centered around the Sabbaths and divided the year precisely into 52 weeks, with four seasons of 13 weeks, for a total of 91 days each. For Jubilees, time was a divine matter that could not be altered by humans.

The Qumran community developed the 364-day calendar even further, adding detailed calculations for lunar phases, the service cycle of priestly families (mishmarot), and the Jubilee years. This calendar was central to their religious identity, and they strongly opposed the lunar calendar used by other Jewish groups. After the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, this calendar tradition perished along with the other sectarian practices of the Qumran community.

The biblical reckoning of time was deeply connected to the religious and agricultural practices of ancient Israel. From the daily cycle to the seven-day week, the Jewish calendar shaped the rhythms of life and worship. While interacting with surrounding cultures, the biblical authors also developed their own unique system that continues to affect Jewish traditions today.

Bibliography

- Ben-Dov, Jonathan. “The 364-Day Year in the Dead Sea Scrolls and Jewish Pseudepigrapha.” Pages 69–105 in Calendars and Years II. Edited by John Steele. Oxbow, 2011.

- ———. “A 360-Day Administrative Year in Ancient Israel: Judahite Portable Calendars and the Flood Account.” Harvard Theological Review 114 (2021): 431–50.

- Miano, David. Shadow on the Steps: Time Measurement in Ancient Israel. Society of Biblical Literature, 2010.

- Stern, Sacha. Calendars in Antiquity: Empires, States, and Societies. Oxford University Press, 2011.

- VanderKam, James C. Calendars in the Dead Sea Scrolls: Measuring Time. Routledge, 1998.