What role did running play in the ancient world?

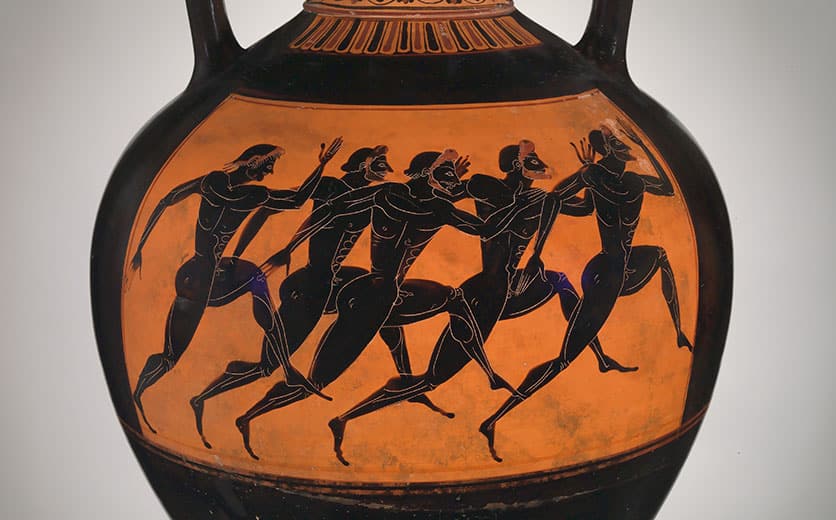

There were many opportunities for running in the Greco-Roman world. Children, young adults, and adults ran as part of everyday athletic activity and as part of sports competitions. Girls ran races dressed as bears in honor of Artemis at the city of Brauron in some periods of Greek history, and there were dedicated footraces for young women and men at Olympia beginning all the way back in the Archaic period (700–500 BCE) and stretching to the imperial Roman period (27 BCE–476 CE). These events were so important that ancient authors such as Plutarch give the birth years of various philosophers and cultural figures in Olympiads. These races would have featured shorter distances like contemporary track-and-field events. The Greek novel Daphnis and Chloe even features a runner named Eudromus (“good runner”), which testifies to the prevalence of the sport in antiquity.

Ancient myth also depicts young people running. In most cases, the runners are fleeing from their unwanted suitors. One story, for instance, speaks of a young woman named Daphne, who runs from the god Apollo and turns into a laurel tree to escape his advances. The laurel crown, the wreath often given to athletic victors, commemorates this pursuit. In another story, the legendary huntress Atalanta challenges potential suitors to a footrace, and she enjoys unparalleled success in defeating her admirers with her “ankle wings.”

Why did New Testament writers mention running so often?

Given its prevalence in Greco-Roman society, it is not surprising that running was a popular image in ancient rhetoric. In the New Testament, one of the most significant depictions of competitive running comes in the Gospel of John (20:1–8). Arriving first at Jesus’s vacated tomb, Mary of Magdala runs to Simon Peter and the beloved disciple to tell them that the tomb is empty. These disciples, in turn, run to the tomb, with the beloved disciple arriving first. Despite “winning the race,” the beloved disciple does not initially enter the tomb, and neither Simon Peter nor the beloved disciple are able to fully interpret the significance of the abandoned burial cloths. Only Mary, who encounters the risen Jesus, is able to understand what has happened and convey this divine understanding to the disciples (20:11–18).

Paul extends the race imagery in 1 Cor 9:24–26.

Do you not know that in a race the runners all compete, but only one receives the prize? Run in such a way that you may win it. Athletes exercise self-control in all things; they do it to receive a perishable wreath, but we an imperishable one. So I do not run aimlessly, nor do I box as though beating the air, but I punish my body and enslave it, so that after proclaiming to others I myself should not be disqualified.

Racing was a popular sport at Corinth, with the Isthmian games attracting hordes of visitors every year and bringing business opportunities for tentmakers like Prisca, Aquila, and Paul himself. It was an elite sport thought by the Greeks to produce beautiful athletes, unlike boxing, which pummeled faces and left broken noses and black eyes. For this reason, 2 Tim 4:7–8 connects the “good fight” and the “race” as the achievement of the letter writer but not necessarily that of all the others earning the crown of righteousness—they have “loved” Christ’s appearance on earth. Paul draws upon this image to portray faith as a race that all may win, regardless of social status. He assumes men and women can equally attain heavenly honors, as long as they exercise self-control and follow Christ. The “imperishable crown” transcends the earthly limitations of the perishable crowns awarded at athletic events, and it reminds audiences that the crown of thorns placed upon the head of Jesus at the crucifixion became a heavenly crown.