The Roman practice of crucifixion apparently began in the time of the Second Punic War (218–201 BCE). It continued until the time of Constantine, who according to the Roman historian Aurelius Victor abolished “the old and horrific punishment of crucifixion and leg-breaking.” To crucify criminals, the Romans suspended the victims’ bodies on vertical beams or on vertical beams attached to horizontal beams across the top. The victim would eventually die, possibly from organ failure, shock, sepsis, dehydration, or asphyxiation. The actual causes are unknown.

What evidence do we have?

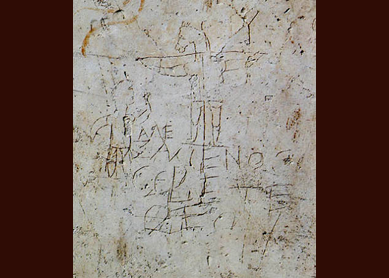

The most ancient graffito of a crucifixion was found in a taberna (inn/restaurant) in Pozzuoli (ancient Puteoli) after World War II. It dates from the era of Trajan (98–117 CE) or Hadrian (117–138 CE) and depicts a woman whose name, Alkimilla, is engraved above her right shoulder (see fig. 1). The cross is T-shaped, with Alkimilla’s wrists attached to the horizontal beam (what the Romans called the patibulum). The woman’s feet are attached on either side of the vertical beam. Whether the graffito depicts a historical crucifixion or a fictional one is an open question.

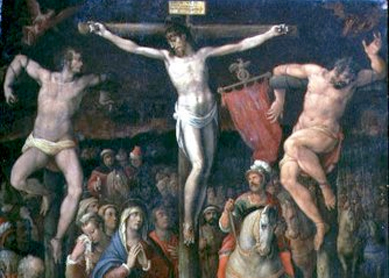

Two ancient skeletons have been found, one in Jerusalem and one in Cambridgeshire, with crucifixion nails in the victims’ right calcanea (heel bones). The sarcophagus in Jerusalem is inscribed with the owner’s name, Jehoḥanan ben Ḥagkol (see fig. 2). The position of Jehoḥanan on his cross was presumably identical with that of Alkimilla—that is, his feet were attached to either side of the vertical beam. There are two other depictions of crucifixion from the Roman era, the so-called Palatine graffito in Rome and the Pereire gem in the British Museum. Both depict T-shaped crosses and victims whose legs are on either side of the vertical beam. However, the Romans could nail (or tie) people to crosses in various ways, and some of Titus’s soldiers attached deserters from Jerusalem to crosses upside down (Josephus, B.J. 5.449–451).

In Roman accounts of crucifixion (which varied, of course), the criminals were often scourged and sometimes tortured with fire. Whips could have bits of bone interspersed in the leather thongs. Criminals could also be forced to carry the horizontal beams of the cross through the streets before crucifixion. The brutality of the tortures before the crucifixion probably helped determine the length of time a victim could survive on the cross. After Jerusalem fell in 70 CE, Titus sent the Jewish historian Josephus to Tekoa. There Josephus saw three friends on crosses. He had them taken down, but only one lived (Vita 420–421). For analyses of Roman crucifixion, see the books by Martin Hengel, Gunnar Samuelsson, and me in the bibliography below.

What was crucifixion used for?

Crucifixion was a penalty used especially for noncitizens, those of low social standing, and slaves. Occasionally it was used for citizens, too. Citizenship was based on a number of factors in ancient Rome, including especially birth, military service, or an emperor’s decree. Crucifixion was also used frequently for those involved in and responsible for seditions. Consequently, it was an obvious choice for Pilate to use crucifixion on Jesus, since he was a noncitizen, of low social standing, and charged with sedition (as indicated by the titulus on his cross, “Jesus of Nazareth, the King of the Jews”; John 19:19; see also Mark 15:26; Matt 27:37; Luke 23:38). Simon J. Joseph, Luis Menéndez-Antuña, David Tombs, and David H. Wenkel have written intriguing interpretations of Jesus’s crucifixion.

Crimes for which one could be crucified were many and diverse. Slaves, male or female, could be crucified for any offense. Others could be crucified for brigandage, arson, desertion, consulting astrologers about an emperor, false accusation, kidnapping, magic, piracy, sacrilege, and so forth. It was a brutal penalty that illustrates the dark underbelly of the Roman Empire.

Bibliography

- Cook, John Granger. Crucifixion in the Mediterranean World. 2nd ed. WUNT 1/327. Mohr Siebeck, 2019.

- Hengel, Martin. Crucifixion in the Ancient World and the Folly of the Message of the Cross. Fortress, 1977.

- Joseph, Simon J. Jesus and the Temple: The Crucifixion in Its Jewish Context. SNTSMS 165. Cambridge University Press, 2016.

- Menéndez-Antuña, Luis. “The Book of Torture: The Gospel of Mark, Crucifixion, and Trauma.” JAAR 90 (2022): 377–95.

- Samuelsson, Gunnar. Crucifixion in Antiquity: An Inquiry into the Background of the New Testament Terminology of Crucifixion. 2nd ed. WUNT 2/310. Mohr Siebeck, 2013.

- Tombs, David. The Crucifixion of Jesus: Torture, Sexual Abuse, and the Scandal of the Cross. Routledge, 2023.

- Wenkel, David H. Jesus’ Crucifixion Beatings and the Book of Proverbs. Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.